The 2018 Smiley Award Winner: Tapissary

The 2018 Smiley Award is presented to Tapissary, a visual artistic language par excellence, created by Steven Travis. Congratulations, Steven!

Voiceless Expression

Steven Travis's conlang journey began the way many other conlangers' have: with an English cipher. Steven's cipher was named Ali, and used English letters (or variations thereof) in different ways depending on their position in the word, or on which type of vowel they came before. He worked with this cipher for a few years starting around 1969, but instead of dropping it, he developed it further, until Ali had become its own full-fledged conlang called Allais. Much like Zhyler, Allais was overstuffed with noun cases (more than thirty), but it served Steven well, and he continued to work with it for several years, eventually changing its name once again to Slavamazic.

Thus far, this story should be familiar to many conlangers. Some quirks of Ali were carried over to Allais, and some of the oddities of Allais were carried over to Slavamazic, but otherwise it was a fairly standard spoken conlang. For Steven things changed when he began to study American Sign Language.

Any hearing person who's studied any sign language will be well familiar with a unique problem one has when it comes to studying. In class, learning a sign language is roughly like learning any other: the teacher models, you watch and repeat, the teacher corrects from time to time, students ask questions, practice dialogues with each other, etc. The difference lies in what the student does at home. Pretty much on day one the student realizes that their usual method of note taking will not suffice. What exactly does one write down? Does one draw a series of images? Perhaps, if the student were a sketch artist, but otherwise there's way too much happening to keep up—especially as one's eyes need to be focused on the signer, not on one's notebook. The problems continue on arriving home after class. Aside from signing in the mirror and reviewing memories from the day, what's one to do? There's no physical homework!

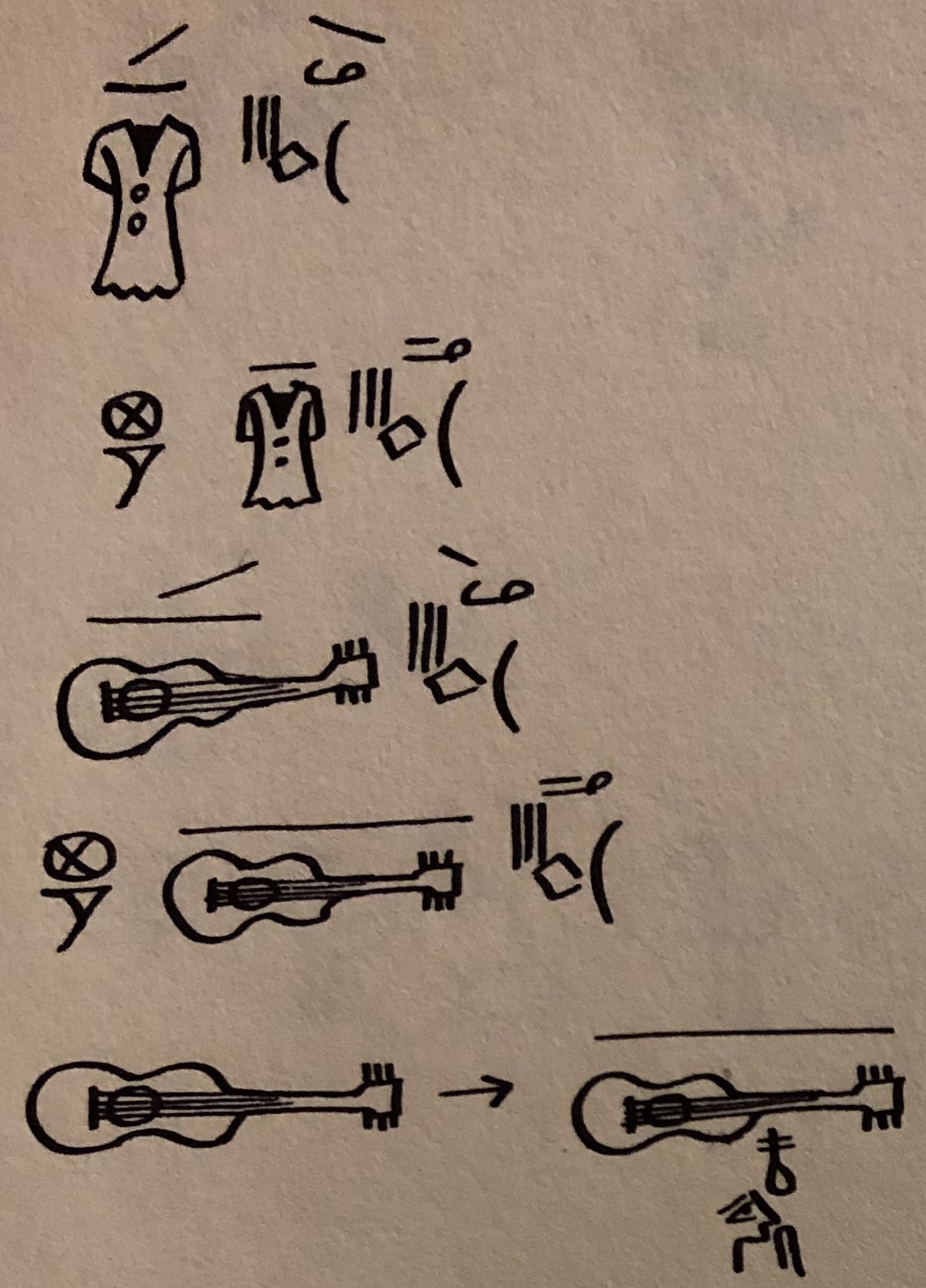

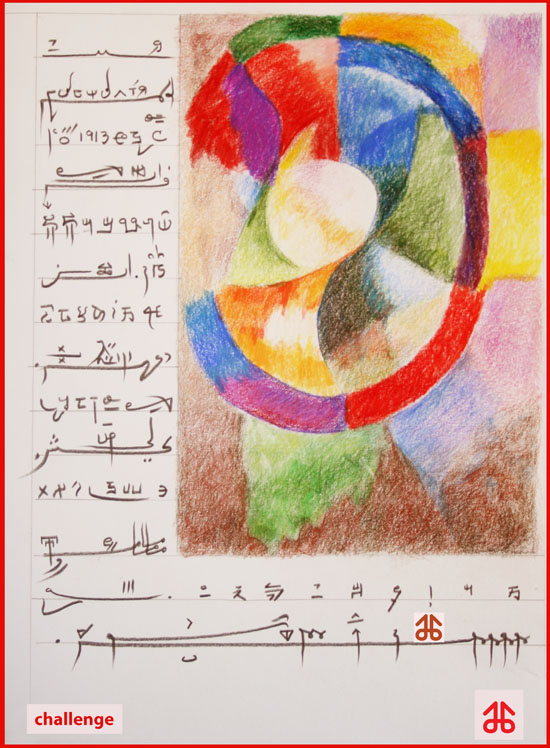

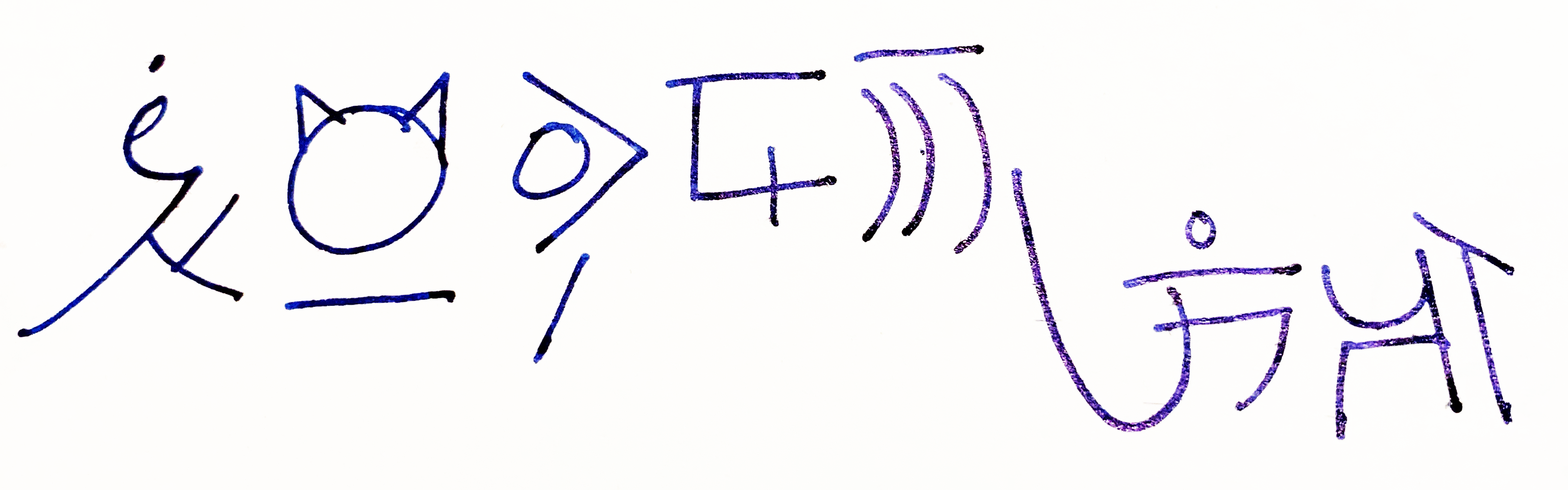

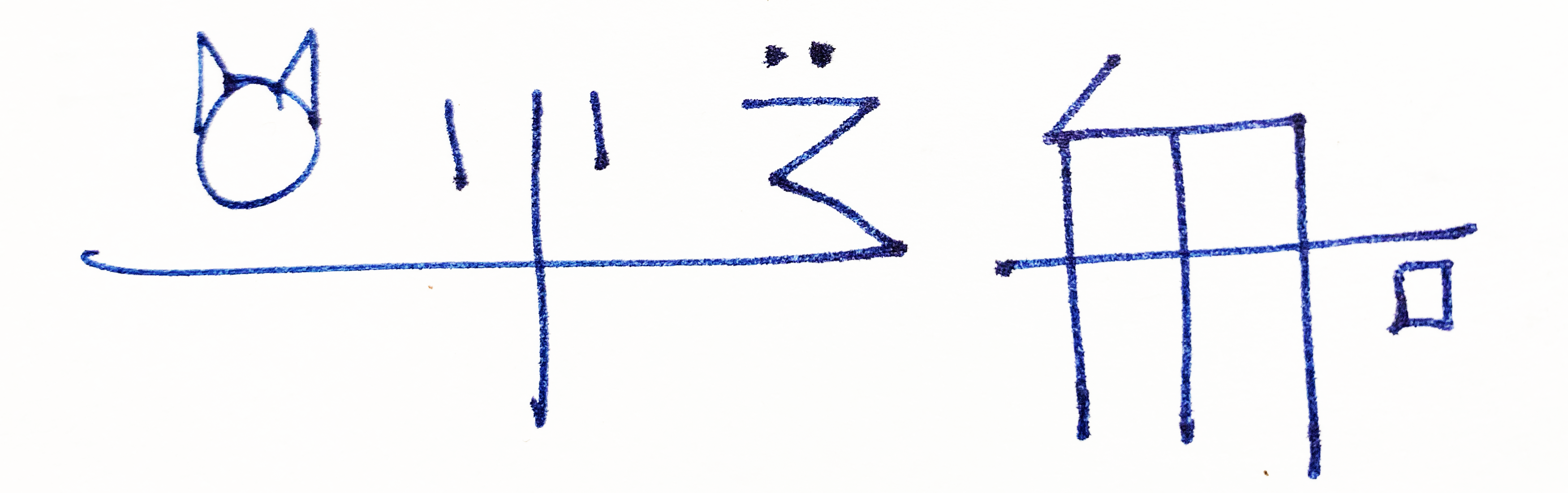

Many have faced this problem, and many have come up with strategies to cope. Steven's went a little bit further than most. He developed a unique blend of drawings and Egyptian hieroglyphs to transcribe American Sign Language. Here's an example, circa 1977:

The next step was the boldest. Steven started writing in this transcription system in his journals, expanding it as needed, and soon it became a full and unique visual language. At first this language was called Yazla, but as he continued to work with it, the glyphs' images evolved, the inventory expanded, and it eventually came to be known by its current name: Tapissary.

First Level Grammar

Tapissary is a lightly inflectional mixed-headed SVO language. In many ways, its grammar mirrors that of English, but that fact belies some of its interesting complexity.

Before delving in, it's important to get a handle on the different modes of Tapissary. It is primarily a written language which, at least initially, had no aural counterpart. It looks like this:

As the language grew, though, Steven decided to add an aural component to it, giving phonological form to the glyphs. In so doing, he borrowed in a lot of words from other languages as well as sounds he liked from the languages he's studied. In addition, though, the grammar of the aural language was built in such a way as to mirror the written form as closely as possible. Let me give you an example.

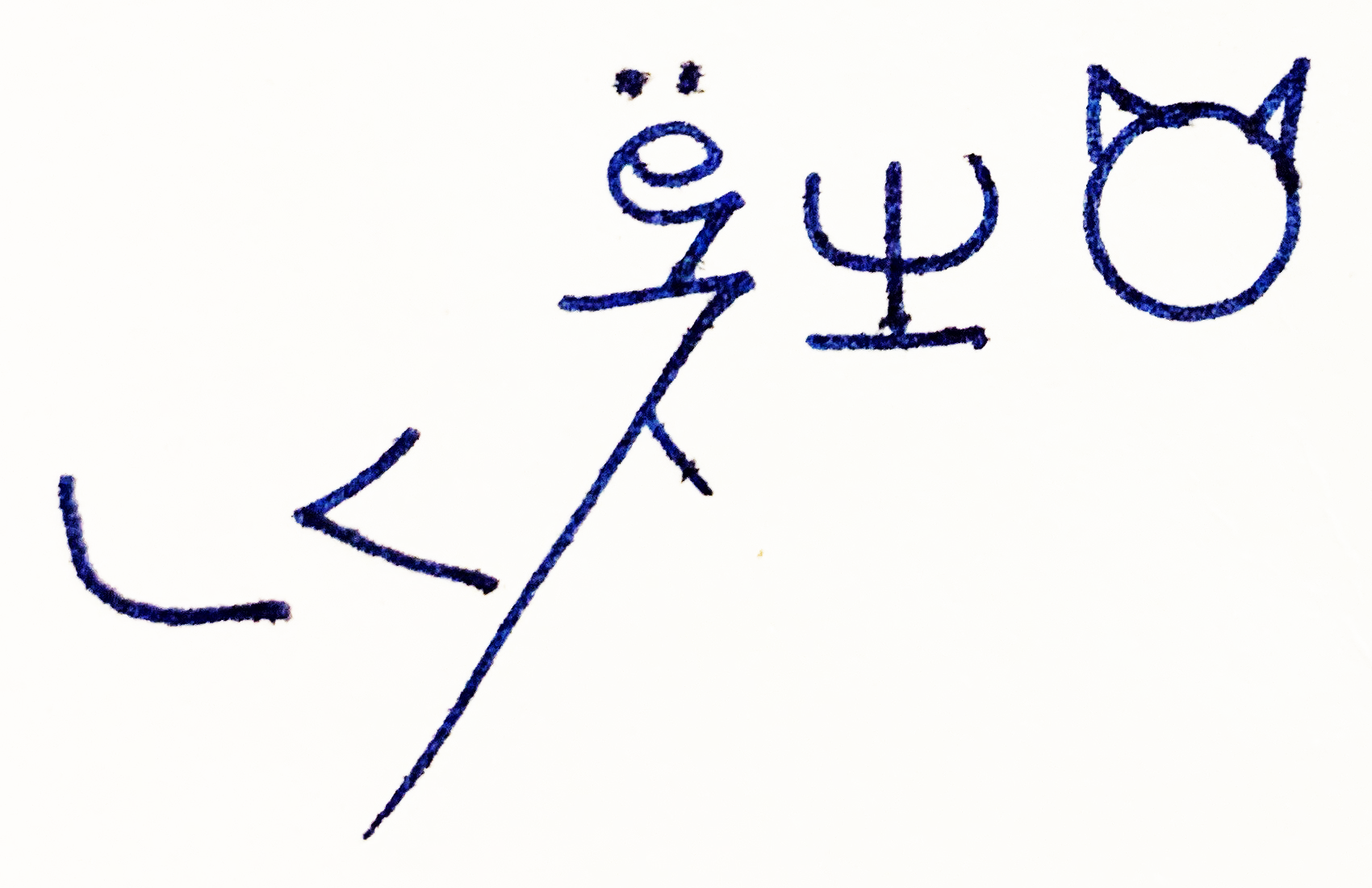

This is the glyph for "cat":

Its spoken form is ratul. (Note: I'm using a romanization system that is basically IPA. It's a bit simpler to understand than the romanization system employed by Tapissary.) To pluralize a noun you add a line over the top like so:

To give the sense of a visual element being added to a glyph when it doesn't follow the linear order (glyphs in Tapissary are written left to right and right to left in boustrophedon style, but both modes are horizontal), the spoken form of Tapissary uses infixes. Rather than the infixes being exclusively prefixing or suffixing, infixes of Tapissary look to the stressed syllable—wherever it is—and infix after it. Thus, in the spoken form, the plural of "cat" ratul is ratuwl, with an infixed -w-.

The same holds for adpositions. Visually, adpositions are separate, but most of them are written either above or below the main glyph, and so they are represented by infixes in the spoken version of the language. Here's how you'd write "the cat is for", "the cat is on something", and "the cat moves onto something" in Tapissary (see below for an explanation about how these adpositions work):

Most of the adpositional infixes aren't semi-vowels, though, so to achieve the same effect, the stressed vowel is duplicated. Thus, "the cat is for" is ratupʀul (the infix is -pʀ-), "the cat is on something" is ratusʀul (the infix is -sʀ-), and "the cat moves onto something" is ratusftul (the infix is -sft-).

If you wanted to say "the cats are for", it's relatively simple to write, as you can easily combine the two visual elements:

In the spoken form, though, it becomes ratupʀuwl. So the spoken language kind of gives the sense of what the written form is like, despite the fact that it all makes a bit more sense if you see the visual form first. I thought this was a very clever feature of the spoken form of Tapissary. These infixes appear for adpositions, verb tenses, and other morphological elements that appear above, below, or within the glyphs of the written language.

A curious element of Tapissary is its series of determiners. While there is one indefinite article bĩ, there are literally one hundred and eighty-six unique forms of the definite article. They are divided into six basic forms, each of which tell you something about the consistency of the modified noun, kind of like a noun class marker. Then each of these six forms has thirty modifications which give you precise deictic information about where that noun is with respect to the speaker. The six basic forms and their functions are as follows:

|  |  |  |  |  |

| zɛ | la | ʀe | ʒi | sø | tø |

| Used with entities that are malleable in form. | Used with liquids. | Used with gasses. | Used with solids. | Used with abstracts. | Used with entities or objects that belong to more than one class. |

With those basics in mind, each of these then can have one of six diacritics that tell you whether the modified noun is (1) touching the speaker, (2) nearby but not touching the speaker, (3) a bit further away from the speaker, (4) far from the speaker but within sight, (5) surrounding the speaker, or (6) cannot be seen by the speaker. Then the form of the definite article itself changes slightly to indicate whether the modified noun is (1) facing the speaker, (2) behind the speaker, (3) to the side of the speaker, (4) above the speaker, or (5) below the speaker. In the spoken form of the language, these form a series of correlatives, not unlike Esperanto, but in the visual form of the language they're rather compact. (You can see them all towards the bottom of the page here.) Furthermore, these articles actually use the physical space of the paper to aid in understanding the deixis of the article. Let me show you an example.

Let's say I wanted to say "I see a cat". Before getting into it, an important note about Tapissary grammar. The indefinite bĩ is basically an adjective. If you want to specify that something is indefinite, first you use a "definite" article to indicate the deixis (if relevant), and then you follow it with bĩ, which indicates that the noun phrase is actually indefinite. So, with that in mind, first one would need to determine what kind of an entity a cat is (obviously a liquid, so we're working with a la determiner). Then you have to determine where the cat is with respect to the speaker (me, in this case). If the cat was not close but not far and to my side, the sentence would look like this:

The spoken form would be Jə dɛn lanot bĩ ratul, literally "I see neither-close-nor-far-to-my-side a cat".

If, on the other hand, the cat was up on something he shouldn't be (Roman!), I would need to use the determiner that indicated the cat was above me. The visual form for that would look like this—with the determiners and cat physically above the rest of the line, but otherwise with the same shape!

The spoken form would be Jə dɛn lalat bĩ ratul, literally "I see neither-close-nor-far-above-me a cat".

Admittedly, it looks better when Steven writes it, but hopefully this gives you an idea of what the language looks like in action.

Second Level Grammar

In many ways, Tapissary is like the separated-at-birth, raised-by-hippies twin brother of Ithkuil (Smiley Award winner exactly ten years ago!). The grammar you've seen thus far merely explains how the language functions. Tapissary has a second level of grammar, called the Cyclic Grammar, which describes how the language is used. To give you an example of what I mean by this, here's the same sentence written several different ways in English:

- I went to Los Angeles.

- I had to go to Los Angeles.

- I got to go to Los Angeles.

- I managed to go to Los Angeles.

- I traveled to Los Angeles.

That's enough to illustrate. In terms of truth value, notice that sentence (a) is a fair summary of sentences (b) through (e). That is, for any of the sentences (b) through (e), the sentence "I went to Los Angeles" is also true. Sentences (b) through (e) merely add a little extra information about either the speaker's attitude about the trip, or how the trip went.

Expressing this type of information morphologically is something Ithkuil is famous for. In natural languages most of it is covered by extra words (as it is in the English examples above). Tapissary does something in between these two strategies. In short, Tapissary allows you to make a decision about how you want to express, say, the speaker's attitude toward what's being said. Once you have made a choice, Tapissary then requires you to use certain words and/or certain syntactic constructions instead of others. These requirements may force you to say things in ways that you never would have expected.

For example, let's say I wanted to focus on how my going to Los Angeles was the beginning of a longer series of events that happened in the day. I might decide to choose the second gesture of the cycle, which focuses on rising action. In so doing, I'll be restricted in the types of verbs I'm allowed to use, so I might say "I introduced a trip to Los Angeles" or "I awakened a trip to Los Angeles". If instead I wanted to focus on the location I was leaving, I might choose the fifth gesture of the cycle, which focuses on falling action, and say "I left my home for Los Angeles". If instead I wanted to focus on the journey itself and how long it took, I might choose the third gesture, the gesture of stasis, and say, "I stood in the traffic on the path to Los Angeles".

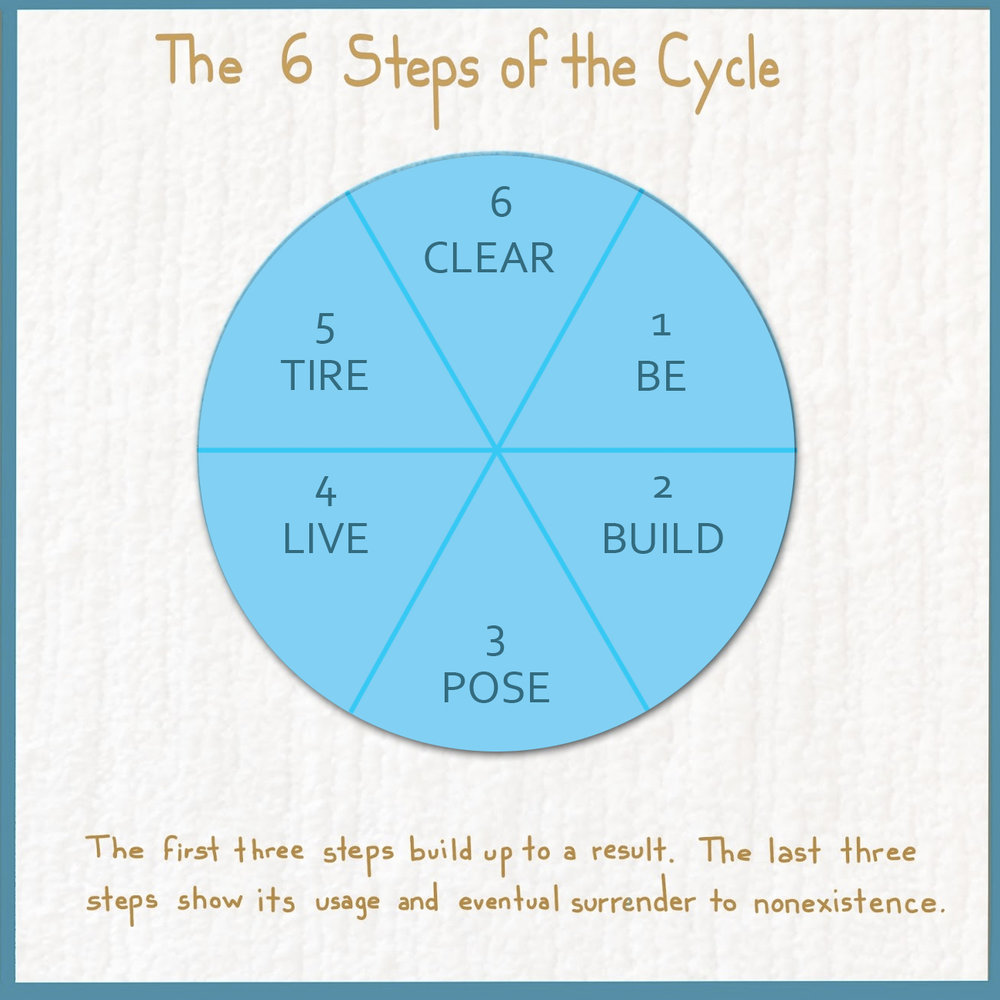

This is what it's like to read Steven's Tapissary compositions. Again, this isn't morphological: It's about word choice. The system can be summarized as follows. The cyclic grammar has six gestures which follow each other in a cycle shown below:

The cycle above is a philosophical notion that all events happen in a cycle where activity/energy waxes and wanes. The consequences of the cycle, though, are far from philosophical, as your verb choice is constrained by the cycle gesture you decide to place your clause in. Here are your choice of verbs depending on the gesture:

- BE Gesture: be

- BUILD Gesture: make, create, build, cook, plot, design, introduce, dig, mate, study, awaken, engage, inspire, integrate, hire, score, nurture, unearth, demonstrate, encourage, reduce, etc.

- POSE Gesture: stand, hold, wait, need, contain, count, await, etc.

- LIVE Gesture: live, see, hear, taste, touch, smell, bleed, breathe, flow, know, work, use, sense, eat, drink, etc.

- TIRE Gesture: leave

- CLEAR Gesture: let, allow

Bear in mind that for the most part, Tapissary is a private language, so the description only needs to make sense to Steven—hence the et ceteras at the end of gestures 2-4. The way I see it, there's a lot that's left to interpretation. It's about how you use Tapissary, and how you interpret both what you're attempting to explain, and how you interpret this second level cyclic grammar and what it means.

Now, hang on to your understanding of this cycle. Remember the trip to Los Angeles. You can focus on the upcoming trip (gesture 2), the journey (gesture 3), or what you're leaving behind (gesture 5). You have to remember that, because now we're going to add a second layer of complexity.

In addition to the six gestures, there are six moods, resulting in 36 gesture types if you use the cyclic grammar (because you don't have to! More on that later). A handy way to remember how the gestures and moods differ is as follows: Gestures replace the main verb of the sentence; moods place restrictions on the phrase types that may be used. Semantically, gestures place the action in a philosophical cycle (waking up is the end of your sleep but the beginning of your day); moods indicate what your attitude towards the action is.

In constructing a sentence that uses the cyclic grammar, you must choose a gesture, and you choose that first. After that, you may choose a mood (leaving it out has consequences, but it can be done), and you'll do that afterwards. The gesture and mood can be from different numbers in the cycle (in fact, they often are). The six moods are as follows:

- No change, or a prepositional phrase is added headed by an abstract preposition: for, with, or within.

- A plural noun is used, or a prepositional phrase is added headed by a preposition of motion: to, toward, until, out of, along, into.

- A genitival phrase is used, or a prepositional phrase is added headed by a preposition of location: in, at, on, under, below, over, above, etc.

- A phrase headed by "as" is used plus a genitival phrase or locational prepositional phrase.

- A phrase headed by "as" is used plus a plural noun or motion prepositional phrase.

- A phrase headed by "as" is used plus either nothing, or an abstract prepositional phrase.

As for the feeling of the moods, they align with the overall cycle: (1) being; (2) interacting/building; (3) results of the interaction; (4) usage/living; (5) waning/lack of interaction; and (6) non-existence/void. How you interpret these and how they interact with what you're saying and how they interact with the gesture you choose is up to you; it's just the word/phrase choice that's fixed.

Let me give you an example of how this works. Let's say what happened is I was on my bed, and my cat Keli, having gotten annoyed with my other cat Roman who was trying to play with her, jumped onto my bed from the floor as a way of escaping him. There are any number of ways I can convey that information. The basic way would be "The cat jumped onto the bed". Using the cycle, I might describe this as the start of Keli's time on the bed. That would be gesture 2: building up to something. Once I've decided that, I can decide on what mood I want to give it. One would be that she's now tense as a result of her interaction with Roman (mood 3). I could also focus on her ending her interaction with Roman (mood 5). Depending on which I choose, the structure of the sentence will differ.

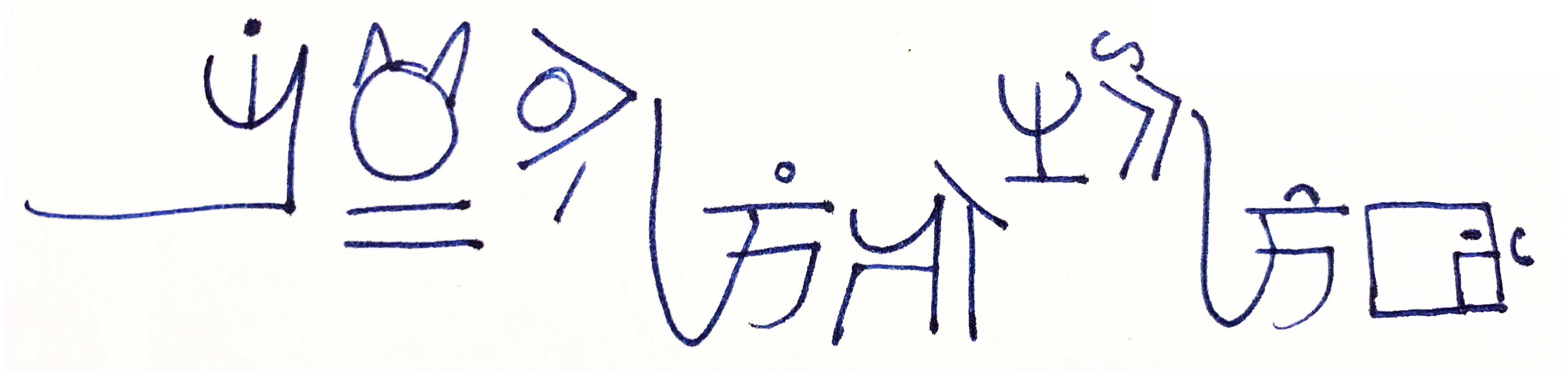

Starting with gesture 2 and mood 3, I could say "The cat awakened her claws on the bed". In the oral form of Tapissary, that would be ʒik ratusʀul mwaʃɛnɛn kãʒo ʀewʀʀǝʀ zazatʃ lɛhɛtto, and in the visual form, it would look like this:

We lose the idea of jumping, but in the flow of the story, we would know that my cat Keli was on the floor. Now she's on the bed, and that she has awakened her claws is an indication that she is not necessarily happy. The fact that it's the third mood let's us know that she is in this state because of her recent interaction. Since it's the second gesture, though, we know this isn't the end of the story, but the beginning of a new one.

A couple other notes on this translation. I changed the definite article before "cat" to emphasize the cat's tenseness (hence describing the cat as a solid). The bed, however, gets the malleable article because cats will dig into that thing with their claws zealously. You'll also notice that the cat is modified by an adposition. This is because adpositions in Tapissary have two parts. When a cat is on a bed, the bed is feeling the weight of the cat, and the cat is placing its weight on it. They're in a relationship. Thus, the cat takes the adposition "on" (i.e. "the being-on-something cat"), and the bed takes an adposition meaning "containing" (i.e. "the has-something-on-it bed"). This is a key feature of Tapissary grammar.

Now, if instead we wanted to do gesture 2 and mood 5, I might say "The cat awakened the bed as a jump from the floor". In the oral form of Tapissary, that would be Tøtʃ ratusftul mwaʃɛnɛn zazatʃ lɛhɛtto bĩ tosbibdir zazas plãkymny, and in the visual form, it would look like this:

Now we're focusing on Keli leaving the floor and gaining the bed. (Also this time I used the combined definite article to emphasize the cat's move from a solid to her natural liquid state.) We no longer have the tension, and instead are focusing on this being the end of her action: the main story was her being on the floor interacting with Roman, and now that's coming to an end (perhaps now she's going to sleep).

Again, all of this is implied simply by the choice of words and their relationship to this philosophical cycle. It's codifying what happens naturally in natural languages (and other conlangs) in a unique and fascinating way. I've never seen anything like it before—and this is just the beginning. For ease of explication, I haven't even mentioned the fiction cycle, which is, in some ways, even more important than the gestures and moods!

In case you were wondering, as I mentioned briefly, you don't have to use the cyclic grammar at all times. You use it to set the tone of a story, and after that you don't need to use it again. You're assumed to be in the same part of the cycle until you signal that you've moved on. This goes for both the gestures and the moods. To invoke a mood, you must use the syntactic configurations indicated, but after that if you don't, it will be assumed that you're in the same mood. That it's optional, though, doesn't make it less interesting. If anything, it's an excellent demonstration of how a grammatical description of a conlang is not the end of the story: How you use it is equally vital.

Linguistic Artistry

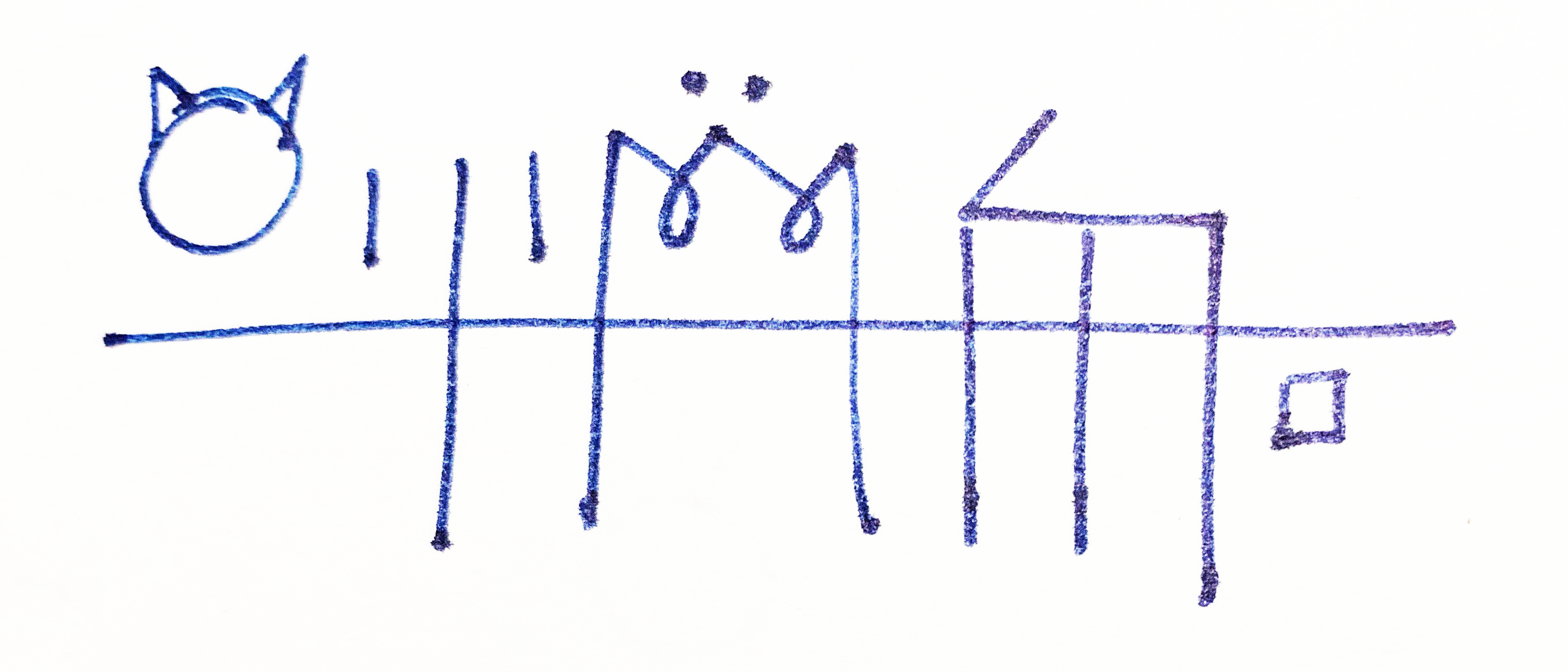

The visuals of Tapissary are the language's initial draw. Steven is an amazing artist, and he blends visual art with his linguistic invention beautifully. One simple way is what he calls the backward script. Tapissary is written in boustrophedon style, but unlike traditional boustrophedon scripts, certain elements of the script change form drastically depending on whether they're being written left to right or right to left. To show you an example, here again is the sentence Jə dɛn lanot bĩ ratul, a version of "I see a cat":

That's written from left to right. Here it is in its backward form:

Glyphs that have backward forms have two variants: One when they start off a phrase called the arm form (it has a long line that runs underneath the main body of text), and another called the pin form that's used when a line from a previous arm form already runs underneath a glyph that would otherwise have a unique arm form. That means you have choices when it comes to how you want to write a backward phrase. The image above is one way to write that particular sentence. Here's another:

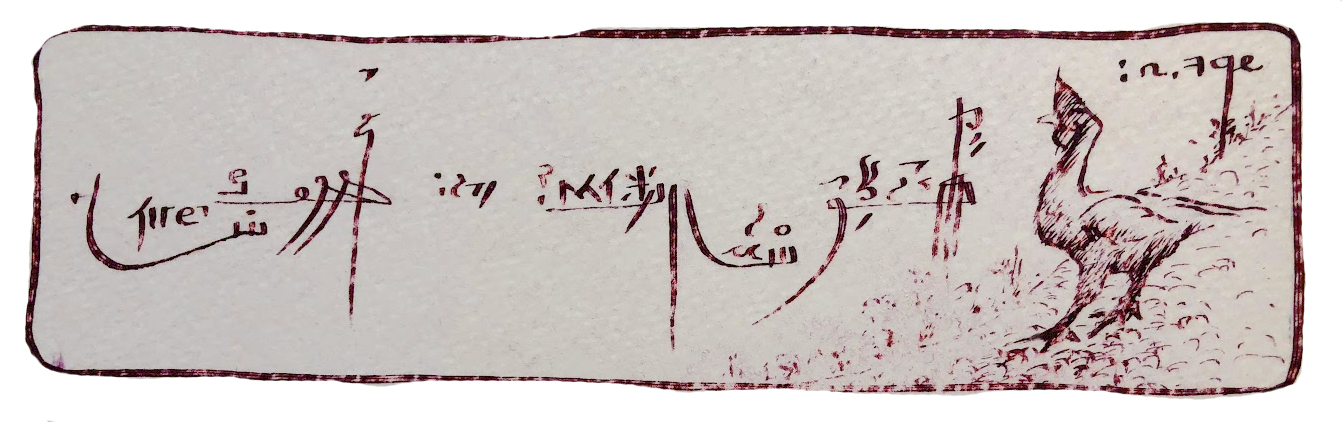

This gives successive lines of text a very distinctive style—helpful if you're the type of person (like me) who skips lines from time to time. To get a good sense of it I'm going to show you some of Steven's amazing artwork, so you can see how all this is supposed to look (as opposed to my chicken scratch. I really thought I'd be better at this, but I guess I need more practice). Enjoy!

There you have the most elegant version of "Why did the chicken cross the road?" that you'll ever see.

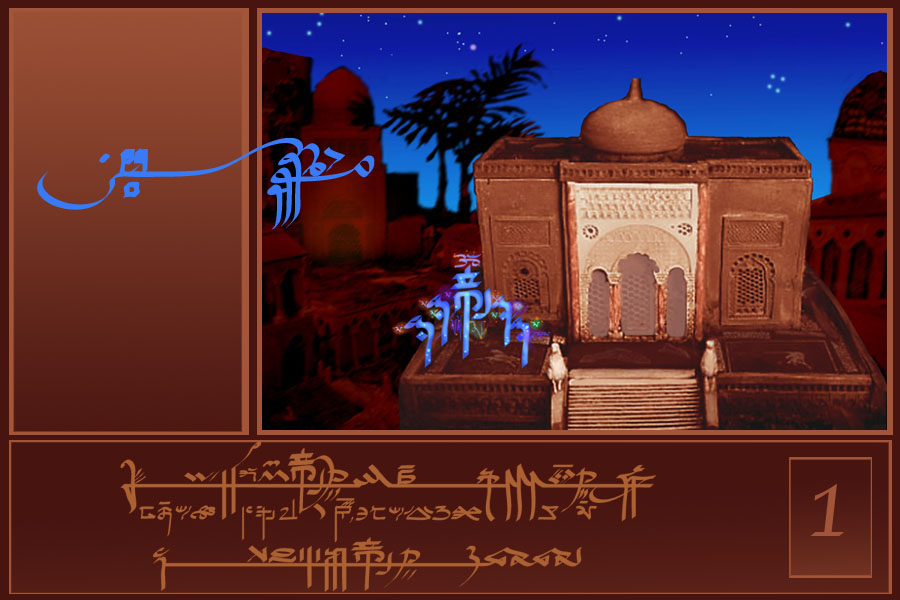

This is a journal entry from around 2015.

Above is the first page of Steven's translation of "The Emperor's New Clothes" (click through for the full version). The whole thing is delightful!

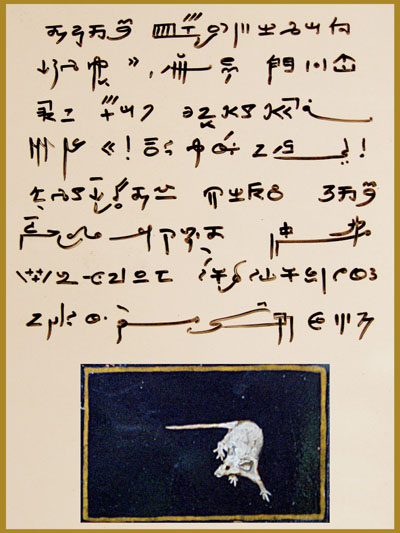

Above is a paragraph from his translation of Alice in Wonderland.

Above is just another journal entry. Steven has reams of this artwork—much of it unscanned! His talent is immense, and the conlanging community is fortunate that one of the ways he chose to express himself is through the medium of Tapissary. It's a gift, and one I've delighted in unwrapping.

How Tapissary Has Made Me Smile

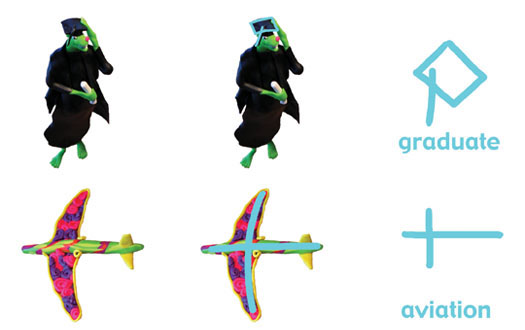

Steven's website is filled with such marvelous illustrations and photographs. Look at some of these illustrations (these are all photographs of little sculptures!) of how the shapes for some of Tapissary's glyphs came to be:

And look at this orange kitty!

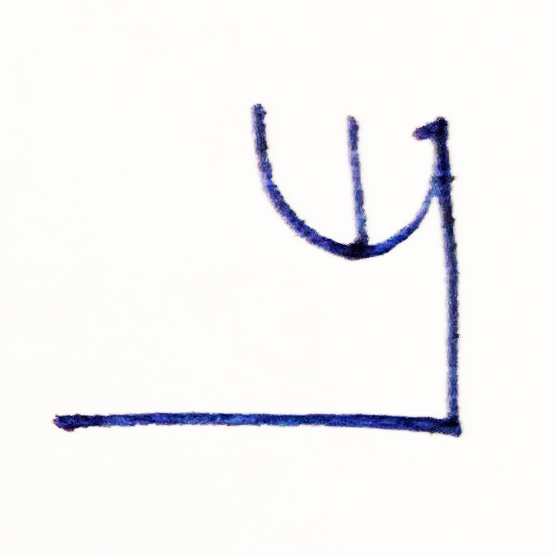

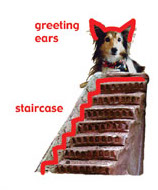

Possibly my favorite thing on Steven's site is his explanation of the origin of the Tapissary glyph for "greet". The glyph looks like this:

And as he explains, upon returning home, his dog would greet him at the top of the stairs. The shape of the glyph is the outline of the dog's ears at the top of a stylized staircase, as he shows here:

It's clear that Tapissary was a private creation, but Steven's public documentation of Tapissary is so wonderfully enthusiastic that it's impossible not to get swept up by it. There's a lot of joy in this language, and that's what comes through to me the most as I go through it. It's been an absolute pleasure to get to know Steven and Tapissary as I did the research for this writeup, and I can't wait to see what the future holds for both. I'm thrilled to be able to present the 2018 Smiley Award to Tapissary. Congratulations, Steven!