Megdevi: An Abandoned Project

This page is devoted to my very first language, Megdevi. This page is here both to explain the language, and to explain why I abandoned the project. The latter may be especially useful to first-time conlangers who want to know what to avoid when creating their first language. Below is a table of contents of topics on this page.

- Introduction: Why?

- How Construction Began

- "Phonology"

- Nouns and Adjectives

- Verbs

- Other Types of Words

- How Sentences Are Formed

- The Megdevi Script

- A Short Translation

- The Golden Knight: An Attempt at Megdevi Literature

- What Now?

- Miscellany

I. Introduction: Why?

Why I created Megdevi is an interesting question, because (and only because) it was my first language. It's always interesting to hear how a language creator came to the conclusion that they needed to create a language, because it really is quite an imaginative leap. It probably doesn't seem so to the language creator (especially those that have been doing it as long as they can remember, which is not the case with me), but to one who has never even dreamt of creating a language, I know it must seem quite bizarre. For that reason, I'll give a brief overview of my history at this point.

In the fall of 2000, I was a sophomore at UC Berkeley, and I was taking my very first linguistics class: Linguistics 5, Introductory Linguistics, taught by Sam Mchombo. At the same time, I was taking French, after having finished a year of Arabic, a semester of Russian, and a semester of Esperanto. The Esperanto class was really an eye-opener, because prior to my learning of Esperanto's existence some time in high school, the thought of creating a language had never occurred to me. Had someone asked me if such a thing could be done, I probably would've said no. The very idea had never entered my head. By the fall of 2000, though, it had, and Esperanto was continually swimming around in my head whenever I attended lecture. Then, one day during a phonetics lecture in Prof. Mchombo's class (at least I think it was a phonetics lecture. May have been morphology...), I was writing in Arabic (a hobby), when I thought to create an Arabic-style IPA. As I was doing that, though, I took a further bodhi tree leap and thought, "What if I create my own language that was like Arabic and Esperanto mixed together?" At that point, the lecture was over, and I started working on the script that would later become the Megdevi script, and I paid little attention to the English class I attended afterwards.

That was how it all began. I was most interested in the script, and creating something that was reminiscent of Arabic, while maintaining the regularity and simplicity of Esperanto.

One issue remains, regarding the "why" aspect, though. If I was trying to create an Arabic-like language, why not give it a name like Al-Rashadazad, or Bin Kartezaazh, or Hassid El-Waqaab, or any other of the myriad thoughtless and insulting names you see in fantasy novels set in some sort of pseudo-Arabian backdrop? Why the name "Megdevi"? This is why.

Being unfamiliar with created languages, I couldn't imagine that one would create a language that wasn't intended to be spoken. As such, it was my intent to use this language I created as a mode of secret communication between myself and my girlfriend at the time. Place special emphasis on the "my" in the phrase "my intent". Though I was intent on creating, she wasn't intent on learning, and this never came to be. Nevertheless, I named it after our two names: Meg(an) + Dav(id) + "-ee" (a pseudo-adjectival suffix). And the name stuck. If I cared about this language, I'd change the name, but I don't, so I won't.

II. How Construction Began

As I said, my goal with Megdevi was to make it seem like Arabic but to be regular and predictable. Additionally, I wanted to be able to convey every semantic concept. An Arabic-style language was ideal, then, because I could come up with a bunch of triconsonantal roots which I could assign to some basic semantic concepts, and then use derivational strategies to devise specific words. So this is what I did. I came up with a series of infixes which represented different types of nouns and adjectives, and then came up with a different set of tense/aspect infixes for verbs. After that, it was just a matter of coming up with affixes.

All the above was done in my class notebooks. Once I started working on the computer, you can actually see how exactly the language developed. The first section is entitled "Rules and such of Megdevi", and lists in chronological order (though that's not what I intended) all the "rules" of Megdevi. It's absurd, and amusing like the 16 rules of Esperanto, so I'll reproduce a few here:

- To form adverbs from non adverbs, add the suffix -ɪtsi after words that end with consonants, and -tsi after words that end with vowels.

- The definite article is ʒi, and it never changes for number or case. There is no indefinite article.

- There are only two cases: nominative and accusative. There are no special forms for the nominative. For the accusative, add -ɪm to the end of accusative nouns and adjectives, -m if the noun or adjective ends in a vowel (i.e.: color).

- All adjectives agree with nouns in number and case.

- All prepositions and postpositions govern the nominative.

It goes on like this. Whenever I thought of a rule, I added it, without a thought to how it would change what I'd done before, or what it predicted for other areas of the grammar. I love that first one. I know that when I first look at a language I've never seen before, the very first thing I want to know is how to form adverbs. That's priceless.

The main point is that the guiding principle for Megdevi was an "and" principle rather than an "or" principle. If I came across something that Megdevi couldn't handle, I simply added it to the grammar. It didn't matter if what I added didn't mesh with what came before, and I never thought to see what problems the addition might create, or, perhaps, what other unsolved problems it might also solve. So keep that in mind as I go through some features of the language itself.

III. "Phonology"

The word "phonology" is in scare quotes because, properly speaking, Megdevi doesn't have a phonology. Instead, it has a list of invariable sounds. In this way, it's like Esperanto, which also lacks a phonology in its theoretical form (in practice, I'm sure there's phonological

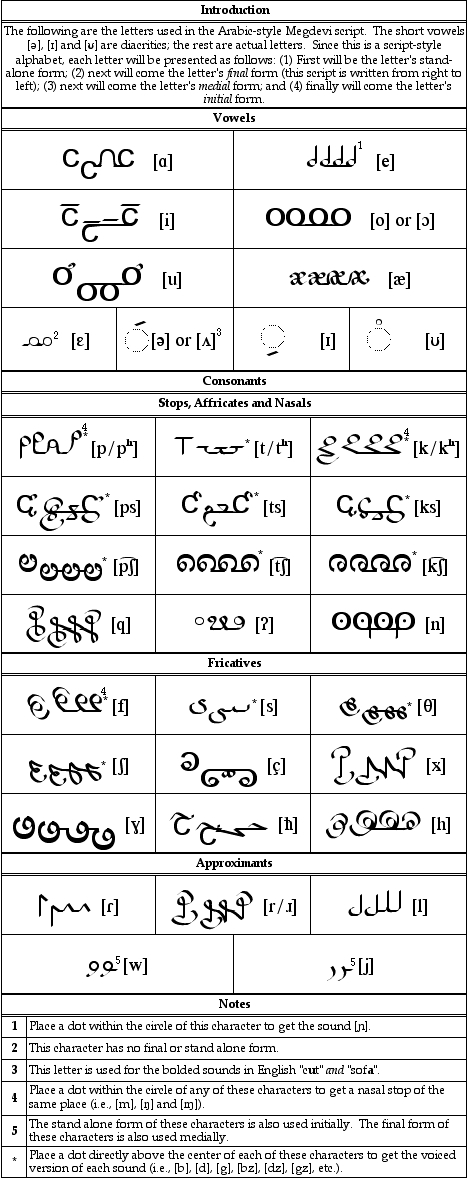

Anyway, as I said, rather than a phonology, what Megdevi had was a list of sounds that the language used. This is a table showing all the consonants:

| Bilabial | Labio-Dental | Inter-dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |

| Stops | p, b | t, d | k, g | q | ʔ | |||||

| "Affricates" | ps, bz, pʃ, bʒ | ts, dz | tʃ, dʒ | ks, gz, kʃ, gʒ | ||||||

| Fricatives | f, v | θ, ð | s, z | ʃ, ʒ | ç | x, ɣ | ħ | h | ||

| Nasals | m | ɱ | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||||

| Approximants | w | r, ɾ, l | j |

The above is certainly an above-average number of consonants, but there are natural languages with more. What's surprising is that all of these are phonemes. That's 43 consonant phonemes in total, unless I miscounted. And further, there was no allophony. So in all situations, no matter what happened, an /s/ sounded like [s]; /t/ sounded like [t], etc. This might be all right if the max syllable of the language was CV, but if two consonant come into contact with each other, things inevitably happen.

And, just to clarify, a triconsonantal root was composed of three of the consonants above. They could be any three, including duplicates. There were no constraints on what could constitute a root. When deriving words, for those who aren't familiar with Arabic or another Semitic language, vowels were put in and around the consonants in various ways, but the three consonants of the root had to appear in the same order (I'll talk more about this later).

Now for the vowels:

| Front | Back | |

| High | i, ɪ | ʊ, u |

| Mid | e, ɛ | ʌ, o |

| Low | æ | ɑ |

Again, there was no allophony. There were two classes of vowels, though. The vowels /ɪ/, /ʊ/ and /ʌ/ were reduced vowels, and the others were full vowels. The main difference between these vowels was orthographic, as the reduced vowels were diacritics while the full vowels were characters in their own right (like in the orthography of Arabic with the long and short vowels). The vowels differed in one respect: If a suffix beginning with a vowel was added to a word ending in a reduced vowel, the reduced vowel was deleted. Otherwise, I believe the vowels just abutted, though I can't think of any examples offhand.

There you have it. That's all that can be said about the phonology of Megdevi. Now onto the structure.

IV. Nouns and Adjectives

This section will go a long way in explaining just how the triconsonantal root system of Megdevi works. Let's say you have a root d-v-d. Any guesses as to what this means? No, not movie: man. You'll see why in minute. Anyway, to get actual words out of this root, you need some vowels. To do this, Megdevi had a number of what I now would call noun and adjective classes. Basically, you take a root with a given semantic meaning, and then an infix series with a given grammatical meaning, and you get a word. So for nouns, the most common were as follows (note: 1, 2 and 3 correspond to the first, second and third consonants of a root):

[Oh, and with your permission, I'm going to use a romanization system similar to Arabic. Thus, [ɑ], [i] and [u] will be aa, ii and uu, respectively, and their reduced counterparts, [ʌ], [ɪ] and [ʊ], will be a, i and u, respectively. All other vowels will be written as they are in the table above.]

- 1e2i3 = a natural noun, e.g. devid "man" (get it?); ðeziʒ "writer"

- 1ii2ej3at = a verbal noun, e.g. diivejdat "maleness"; ðiizejʒat "writing"

- 1æ2i3 = a utility noun, e.g. ðæziʒ "writing utencil"

- 1ii2ɛ3 = a place noun, e.g. ðiizɛʒ "writing studio"

- 1aa2o3 = an object noun, e.g. ðaazoʒ "a written document"

These were the most common nouns. However, there were an endless number of nominal affixes to make new nouns. So, from the word for "man", devid, you could get:

- devidudʒ: mankind

- devidælɛf: man in charge

- devidotsum: a container for men

- devidɛks: big man

- devidiitsiij: small man

- devidaahen: worthy of being called a man

- triidevid: husband

- viidevid: young man

- diidevid: not a man

- zodevid: woman

- glidɛdevid: young man

- θodevid: someone who's about to become a man (pre-bar mitzvah?)

- ʃaajndevid: former man

True, many languages do have a lot of derivational affixes, but not like this. Further, whenever I thought up a new idea (so maybe a titled person as opposed to an untitled person), I would add a new affix. That's not the way to go about doing things.

As a segue into adjectives, I'll introduce numbers. I actually came up with an absurd amount of templates for numbers, and I have no idea why. The result is the most fully fleshed out number system I've ever created. This is some of it:

- 1aa2u3 = ones column, e.g. daatsul, "six"

- 1aa2ej3 = tens column, e.g. daatsejl, "sixty"

- 1uu2ii3 = hundreds column, e.g. duutsiil, "six hundred"

- 1a2o3 = thousands column, e.g. datsol, "six thousand"

- 1ii2ii3 = millions column, e.g. diitsiil, "six million"

- 1o2aa3 = billions column, e.g. dotsaal, "six billion"

- 1oj2aj3 = trillions column, e.g. dojtsajl, "six trillion"

- 1o2o3on = quadrillions column, e.g. dotsolon, "six quadrillion"

And, again, there were affixes:

- daatsuliift: a sixth (fraction)

- daatsuliin: sixth (ordinal)

- daatsulidiil: hexagon

- daatsulikol: cube (for example)

And there were even time-related templates:

- 1oj2u3 = years, e.g. dojtsul, "six years"

- 1aa2uu3ow = decades, e.g. daatsuulow, "six decades"

- me1ii2i3in = centuries, e.g. mediitsilin, "six centuries"

- 1aaj23ɛθ = millenia, e.g. daajtslɛθ, "six millenia"

- 1ii23iks = hours, e.g. diitsliks, "six hours"

- 1uu2ɛ3 = minutes, e.g. duutsɛl, "six minutes"

- 1o2æ3 = seconds, e.g. dotsæl, "six seconds"

I hadn't gotten as far as milliseconds, but it would have eventually become a necessessity (well, unless I could use the fraction suffix...). Again, taken separately, some of these templates and affixes are not so unreasonable. Taken as a whole, they begin to disturb one (or at least this one).

I'll conclude this section with adjectives. They work the same way as nouns, but they behave like adjectives. Here are the most common:

- 1a2ii3 = natural adjective, e.g. daviid, "male"

- 1u2uu3 = nominal adjective, e.g. duvuud, "manly"

- 1a2ii3ad = verbal adjective, e.g. satsiizad, "burning"

- 1uu2æ3 = object adjective, e.g. suutsæz, "burnt"

- 1æ2ɛ3 = place adjective, e.g. sædɛs, "circus-like" (cf. siidɛs, "circus")

- 1ii23a = color adjective, e.g. diivda, "man-colored"

As you can see, the verbal adjective and object adjective are more like present and past participles, than anything else. Additionally, there are a number of affixes which turn other forms into adjectives, but there weren't many for modifying adjectives.

That's basically how the nominal/adjectival system works. How these things are put together into phrases and sentences will be discussed later.

V. Verbs

The basic idea for how verbs work isn't bad. The realization is kind of phony and obviously inspired by Esperanto and English, but the idea itself isn't too bad. I'll now describe the system.

To begin with, a verb could come in one of two aspects: Perfect and non-perfect (not "imperfect", because it has a preterite reading in the past). The difference lie in the vowels that were inserted in between the three consonants of the root. I'll use the root g-r-ts related to "biting" as an example:

- 1a2a3 = the non-perfect stem, e.g. garat, "bite"

- 1i2i3 = the perfect stem, e.g. girit, "have bitten"

This gives you two stems. To these stems, suffixes are added to express tense and...mode, I guess. Not sure how exactly to classify it, but the suffixes correspond one-to-one with the tenses of Esperanto. Here they are:

- -ii = present, e.g. garatii, "bites"; giritii, "has bitten"

- -uu = past, e.g. garatuu, "bit"; girituu, "had bitten"

- -aa = future, e.g. garataa, "will bite"; giritaa, "will have bitten"

- -o = subjunctive, e.g. garato, "would bite"; girito, "would have bitten"

- -a/-i = imperative, e.g. garata, "bite!"; giriti, "have bitten!"

Never mind that that last one doesn't make much sense. This is how the tense system works. You'll find that it works very well with English and Esperanto.

In addition to marking tense, Megdevi also marks something that Esperanto marks, but other European languages don't: transitivity. How this was marked, though, depended on the nature of the verb. So, if a verb was naturally transitive, it could take an intransitive marker to make an intransitive action. If the verb was naturally intransitive, though, it'd take a transitive marker to make it transitive. How did I determine whether a verb was naturally intransitive or transitive? Quite frankly, looking at some of these verbs now, I have no idea. Nevertheless, these are the markers:

- traa- = transitive marker, e.g. traagaratii, "bites (something)"

- dʒa- = intransitive marker, e.g. dʒapawafii, "serves (no object)"

In addition, there was a passive suffix to make a verb passive (there was also an inchoative infix which I won't bother listing):

- -iis = passive, e.g. garatiisii, "is bitten"; giritiisii, "has been bitten"

And that's about it for verbs. There are derivational suffixes, but they're not terribly interesting. The only other thing to mention about verbs without going into sentence structure is that the direct object of every verb was marked with the accusative, except for one: matsala, "to be". The semantic role of either the subject or object didn't matter: It was simply the grammatical object that was marked with the accusative suffix -im.

VI. Other Types of Words

Other types of words include prepositions, pronouns, conjuctions, etc. They're not that interesting in Megdevi, so I'll just discuss them briefly.

Preposition were whole words that could take on pretty much any form I wanted. Sometimes they belonged to certain triconsonantal roots; sometimes they didn't. For example, the prepostion wii means "with respect to" or "regarding", and belongs to no root. The preposition snɛs, though, which means "still", belongs to the root s-n-s, which actually means something like "still" (the derived verb means "to be still x", where x is a verbal noun). Nothing constrained the creation of prepositions. Whenever I thought of a new sense of English "for", for example, I'd create a new preposition with specifically that meaning. If I'd continued on in this way, Megdevi would have ended up having as many prepositions as roots.

On the subject of prepositions, there was one postposed element in Megdevi. It was formed by putting a circumfix on any given word (though usually a noun) and postposing it to a noun. The resulting form is a possessed

In both the case of prepositions and the case of the postposition, nouns that were modified by an adposition were put in the nominative case. Thus, I believe if the object of a verb was in the construct state, it took no accusative marker.

Conjunctions were similar to prepositions, in that whenever I thought up an interesting conjunction I invented a form for it. For example, I had two distinct forms for "while" and "meanwhile". I'm pretty sure the latter isn't a conjunction in English. Oh well.

Pronouns in Megdevi were very simple. Ordinary pronouns ended in -oj and possessive pronouns ended in -ojiij. Both could take the accusative suffix. For the rest of the form, you attached any number of consonants to the front to get a different pronoun. The common ones were ʔoj "I"; ʒoj "you (both singular and plural, like in English)"; roj "he"; moj "she"; doj "it"; noj "we"; and ðoj "they (all genders, like English)". In addition, I also had pronouns for a general third person argument, a reflexive third person argument, and for reference to a divine entity as a third person argument. Had I kept with the language when I learned about animacy, I probably would've added pronouns for animate and inanimate arguments, mammals vs. birds, etc.

Similar to the pronouns were the "correlatives". This word should raise a red flag, because the only place I've ever seen this word is in Esperanto. In Esperanto, there are five prefixes and eight or nine suffixes which you combine in various ways to get words like "anywhere", "who", "that", etc. Megdevi does the same thing, only with more categories. So, sticking just with the "thing" category, you could get the following:

- Negative: dim, "nothing"

- Interogative: lim, "what"

- Demonstrative (Proximal): θim, "this thing"

- Demonstrative (Distal): gim, "that thing"

- Indefinite Exclusive: mim, "something"

- Indefinite Inclusive: ʔim, "anything"

- Universal Exclusive: tʃim, "each thing"

- Universal Inclusive: sim, "everything"

- Definite: ʒim, "the thing"

This should give you an idea. In addition to "things", there's "individuals", "kind of" (e.g. "this kind of x"), "places", "way" (e.g. "do it that way"), "amount", "reason" (e.g. "for any reason"), and "time". Now, there are actually languages that build up correlatives (if you want to call them that) in this way. However, I think one would be hard-pressed to find a natural language that did it in such a specific way (semantically. There are languages that do so phonologically in exactly a manner like this).

That does it for the words of Megdevi. There are other patterns, but chances are if you encounter a Megdevi word, it'll be one of the type already discussed on this page. Now I'll say a little bit about how sentences are formed.

VII. How Sentences Are Formed

This will be a very short section, because it's very simple. If you separate Megdevi into noun phrases, prepositional phrases, verbs, and adverbs, then word order is completely free. There are no constraints at all. So, let's take a complex sentence and see how many orders we can get (and, note, all of these are pragmatically identical). Let's do the sentence, "A man (devid) quickly (nabziilitsii) gave (dʒanaru) a book (saasolim [in the accusative case, recall]) to (ʔɛdʒ [just like in English]) a girl (megits) on (kaaldʒ) the grass (ʒii seliʃ)":

- devid nabziilitsii dʒanaru saasolim ʔɛdʒ megits kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ.

- nabziilitsii devid dʒanaru saasolim ʔɛdʒ megits kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ.

- saasolim devid nabziilitsii dʒanaru ʔɛdʒ megits kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ.

- saasolim devid nabziilitsii dʒanaru kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ ʔɛdʒ megits.

- saasolim devid nabziilitsii kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ ʔɛdʒ megits dʒanaru.

- saasolim nabziilitsii kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ ʔɛdʒ megits dʒanaru devid.

- kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ saasolim nabziilitsii ʔɛdʒ megits dʒanaru devid.

- kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ saasolim nabziilitsii dʒanaru devid ʔɛdʒ megits.

- nabziilitsii kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ saasolim dʒanaru devid ʔɛdʒ megits.

- kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ ʔɛdʒ megits saasolim dʒanaru nabziilitsii devid.

This is just ten of the seven hundred and twenty possible word orders. (Thanks to Yahya for helping me math it out!) As you can see, the constituents can be ordered in whatever way one feels like. Among the highlights of the above are sentences (1) and (10), which are inverses of each other (not exact, but constituentwise). It's not terribly realistic for a language to do this, but I've heard of one or two in Australia that can, so it's not impossible.

Now for the impossible: Megdevi actually had free word order. How is that different? This is how:

- ʔɛdʒ devid nabziilitsii dʒanaru saasolim megits kaaldʒ ʒii seliʃ.

- ʒii nabziilitsii megits seliʃ devid dʒanaru saasolim ʔɛdʒ kaaldʒ.

- devid dʒanaru kaaldʒ megits nabziilitsii saasolim seliʃ ʒii ʔɛdʒ.

The astute reader will note that the above is, in fact, impossible. Each of the sentences above is supposed to mean the same thing as each of the sentences in (1) through (10). However, sentence (11) would seemingly mean, "A girl gave a book to a man on the grass". Then (12) just gets crazier, and (13) is what the sentence would look like if you arranged the words in English alphabetical order. Nevertheless, this was allowed. I wanted total flexibility of expression, and, I reasoned, if you had enough context, you'd be able to recover the intended meaning from sentences as disfigured as (13). I guess the reason why one would say/write a sentence this way is...I don't know, to be a jerk? Actually, I had just gotten finished reading Ulysses when I started Megdevi, so I was very much into being able to express any idea in as many ways as possible, so freedom of word order was important to me. Of course, had I known anything about cases and agreement, I might have created a language that could feasibly have free word order, but I didn't know much about...much of anything at that point. I was just getting started.

Before moving on to other matters, I'll mention briefly some other constructions. First, two verbs could modify one another. I'm having trouble finding examples, so I'll just make one up, since this is basically how it worked:

- Step 1: Take a verb which can modify another verb, like kajala, "to want".

- Step 2: Take another verb you want to modify, like talaja, "to tell".

- Step 3: Turn the second verb into a noun: talaja becomes tiilejjat.

- Step 4: Put the first noun before the second, and attach an accusative suffix to the second: kajala tilejjatim.

- Step 5: The subject of the sentence comes first, and is unmarked: devid kajalii tiilejjatim, "A man wants to tell".

- Step 6: Since there's already a noun marked with the accusative, prefix the object of "tell" with li-: devid kajalii tiilejjatim limegits, "A man wants to tell a girl".

- Step 7: Voila.

Don't ask me how you'd say, "A man wants to tell a girl a story about whales", because I forget. More li-'s would be involved. I actually really like the sound of this kind of construction, which, without any consonants in there, would be (in the present tense): 1a2a3ii 1ii2ej3atim. I'll have to see if I can borrow it into a different language in the future.

Just to round off our discussion of sentences, I'll briefly mention relative and subordinate clauses. They're also done with the all-powerful prefix li-. So if this is "A man

- devits kajalii megitsim.

Then this is, "A boy who likes a dog (bedijim) likes a girl" (I'm leaving out plurals and definite articles because I don't want to go hunting for the unicode designations for the characters I'd need):

- devits liroj kajalii bedijim kajalii megitsim.

So what you do is you attach the prefix li- to a pronoun corresponding to the target of relativization (in this case, devits, "a boy", so the pronoun is roj, "he"), and you put this complex directly after the target of relativization. You then inflect the pronoun for whatever case it needs (in this case, it doesn't need one, because it's the subject), and then the sentence proceeds as it normally would, with a gap where the target of relatization would be (in this case, that gap is right where the subject is, so there is no gap). This method of forming relative clauses is actually similar to Arabic, so it works and doesn't seem too bizarre. Here's how the sentence "A boy whom a dog likes likes a girl" would look:

- devits lirojim bedij kajalii kajalii megitsim.

In this sentence, the pronoun takes the accusative case, since it's the object of the embedded verb. Remember, though, that word order is free, so you could put the subject bedij after the verb to avoid two instances of the same verb in a row.

Finally, subordinate clauses worked just like in English, with li- taking the place of "that". So working with our verb talaja, "to tell", here's what a sentence with a subordinate clause in it would look like:

- devits talaju megitsim, libedij kajalo mojim.

The sentence above means (word-for-word), "A boy told a girl that a dog liked her". The -o suffix on the verb is that subjunctive suffix that I always went back and forth on. Sometimes I would use the subjunctive, sometimes the same tense, sometimes the present... Kind of like in English.

That's all there is to know about how sentences are formed. Really. In fact, that's all you need to know about how to use Megdevi. Really. Armed with this information and a dictionary, you can translate any text. I'll demonstrate this for you later by showing you some of my translation of Shakespeare's The Tempest. For now, though, I might as well go on to the script.

VIII. The Megdevi Script

Megdevi's script is the only thing that's survived the Megdevi language implosion. Why? Because, as it turns out, it's perfectly suited to writing English. The script is an Arabic-style script (written from right to left) that has a character for each of the sounds listed in the "Phonology" section above. Now take a look at those sounds. Remembering that, in my English, there is no such vowel as [ɔ] (so "caught" and "cot" are identical), you should be able to see that there is a letter for every sound of my English, plus some. [Note: The /r/ in Megdevi could be pronounced as a trill or like an English "r".]

The foregoing is relevant because, unlike any of the other scripts I've ever invented, Megdevi's script is actually in use. Specifically, I use it to write in English. Why? Partly because I can; partly because every so often I want to write a note in class that I don't want anyone else to read (e.g. "Jebus, he actually takes this OT thing seriously!"). As a result, the Megdevi script has evolved so that it's easier to write.

First, this is what the old version looked like (I'm going to be lazy and just put up the image of the script that's currently hosted on Langmaker.com):

Before giving you an example of how the script has changed, here are some critiques of the script itself:

- The vowel [ɛ] is somewhere halfway between being treated by the orthography as a full vowel and a diacritic/reduced vowel. There doesn't seem to be any principled reason why that is.

- Just about every voiceless/voiced pair is represented by a dot being placed over the voiceless character, but that isn't the case with the pair [x] and [ɣ]. This isn't improbable for a script, but it seems highly unlikely that it would happen with such a seldom-used pair.

- In non-careful writing, there's little difference between [x], [ɾ], [ɑ], [s] and [h] (and possibly even [l]). This would surely cause legibility problems.

Now, for how the script has changed. This will be easiest to explain in list form:

- The initial and stand alone forms of [u] now look much closer to Greek lower case non-final sigma, σ , but turned about 30° to counterclockwise.

- The medial and final form of the [p] series has changed. Seeing as the medial form, when written out, causes one to go over a line one has already written and slows down writing time considerably, I changed the form so that it looks like the initial form, but ends with a flourish. As a result, the medial form no longer connects to the following letter. The final form changed so that it looks just like the medial form.

- In practice, writing the medial form of the [ps] series actually proves to be rather difficult. The final form, however, works rather well, even though it involves line crossing. Therefore, the medial form has changed to look like the final form, and looks like a small 8 inside a large 8.

- The final form of [n] is now triangular (specifically, a right triangle whose hypotenuse connects the base line to the uppermost portion of the character. The final side descends below the base line).

- Homorganic nasal + stop clusters (bilabial and velar only) have acquired a special form. Because bilabial and velar stops are distinguished from nasals by simply a dot, it can be difficult to read (and redundant to write) a sequence of a bilabial or velar nasal followed by a homorganic stop. And, since this is used to write English, such clusters pop up a lot. As a result, clusters are now represented with a ligature. To indicate a nasal followed by a voiceless stop, a horizontal line is added to the top of either a [p] or a [k] (it rest right on top, the way the vertical line rests right on top of the vertical line for [t]). To indicate that the cluster is a nasal followed by a voiced stop, you put a dot over the line.

Below are two images. The first shows an image of a word written in the old version of the Megdevi script (using the font), and the second shows that same word in the revised version of the Megdevi script. First, the old version:

![]()

And now the same word in the new version of the script (as written by me, though it's somewhat unnatural):

The word is just a nonsense word used to illustrate the characters that changed: fiimaapsyuuŋgen.

Even though the font represents an older version of the Megdevi script (and is, quite frankly, a nightmare to navigate), you can download it by right-clicking here (for a .zip version, left-click here).

By way of concluding, the script of Megdevi is the only portion of the language that survived. The script isn't perfect (if I were to design an Arabic-style script for English right now, it'd look much different), but, perfect or not, I use it all the time. That, in itself, makes it somewhat interesting. Also worthy of note, though, is a comment to script-makers that Mark Rosenfelder actually makes on his Language Construction Kit, which I'd like to echo here. To make your script real, whether it's intended for a conculture or personal use, you really need to practice writing in your script a lot. There's just no way I could've predicted the above-mentioned changes for Megdevi's script, but they occurred organically, and are quite natural. Thus, by simply using it, the script has become more real. I recommend that anyone who invents a script for serious use (or for a conculture that's supposed to use it seriously) try out the invented script for a long period of time. The changes the script will undergo just might surprise you.

IX. A Short Translation

As promised, this section is devoted to an excerpt from Shakespeare's The Tempest, which I began to translate into Megdevi (I never finished, because I finally realized that the "translation" was silly). The point will be to show what Megdevi looks like in action, and to show more fully why it was set aside.

First, a comment on the play. Shakespeare wrote a good number of plays during his tenure, and The Tempest was the very last, according to many. [At least some say that Henry the VIII was co-authored by he and another, and rumours abound that he wrote under an assumed name even after his retirement. Of course, there are also rumours that there was no Shakespeare. That's academia for you.] I like to think of The Tempest as Shakespeare's last play, because it seems appropriate. The play is about an exiled "magician", if you will, Prospero, who is exiled by his brother, condemned to live on an island where he reigns supreme with his arts. Realizing that his daughter, Miranda, can't live an isolated existence and needs to get on with her life, Prospero engineers it so that a suitor is brought to the island for Miranda and they both are unexiled, and, as a result, Prospero permanently gives up all his magic, and "retires" to an ordinary existence.

Not being a big fan of Shakespeare, I was surprised to discover how much I liked this play, in particular. Maybe it was the "last hurrah" feel of it; maybe it was how intriguing a character Prospero is. Maybe it's because it's quoted in "The

Below you'll find an excerpt from my translation. I don't have much to choose from, because I don't think I even got out of Act II, but it's enough to look at and criticize. In this section from act I, scene ii, Prospero is consoling Miranda over the recent shipwreck. He explains to her that he's the one that caused the shipwreck, but that he made sure no one was harmed, and that he did so for a purpose. After this, he goes on to tell her what the purpose

First, I'll do the section in English (Shakespeare's English), then I'll do it in Megdevi, then I'll give an interlinear. First up, English:

'Tis time

I should inform thee farther. Lend thy hand,

And pluck my magic garment from me. So:

[Lays down his mantle]

Lie there, my art. Wipe thou thine eyes; have comfort.

The direful spectacle of the wreck, which touch'd

The very virtue of compassion in thee,

I have with such provision in mine art

So safely ordered that there is no soul—

No, not so much perdition as an hair

Betid to any creature in the vessel

Which thou heard'st cry, which thou saw'st sink. Sit down;

For thou must now know farther.

In my notes, it says that those are lines 32 through 39. I somehow doubt it. I can't count the line numbers that easily in my edition, and I'm too lazy to look it up online. It's around line 30, though. Anyway, this is the Megdevi version:

matsalii ʒulo,

liʔoj θafasii liʒoj liɾejjatim trænts. nejinim θaŋaka-

lapsanasa ʔojiijim daziinim gæriθim. θæɾuu:

[traatasafii rojiijim qæsimim]

tasafa gaa, ʔojiij ʒiinejksat. ksalawa ʒoj kelisæʒim; ʔɛtsedʒafalafa.

ʒii naaroɣ ʔaaʒaasoθzahiiʒuθ, lidoj lɛnt

ʒoj laʃaθuu ʒuu hiijejʃat ʔaamiijejʒatuuθ,

ʔoj, paatʃ ʒojiij ʒiinejksat ʒaaθiintsaaloʃuuʃ

ʔɛks pariizitsii psiliksii, riks matsalii diijx ʒeziθ—

diijx, dii fejiʃosk kaaldʒ dejl metsil lɛnt ʒii ðænts

lidoj ʒoj traabazavuu jiixejdatim

lidoj ʒoj jasaθuu kiilejpsatim. raakkanatʃa,

tʃuu naajk ʒoj ranasii viiʒejsatim trænts.

And now for the basic interlinear:

is the-time,

that-I should (to)-you (INFIN.)-inform-ACC. further. hand-ACC. lend-

and-pluck my-ACC. magic-ACC. garment-ACC. so:

[TRANS.-lays-down his-ACC. mantle-ACC.]

lie there, my art. wipe you eyes-ACC.; INCEP.-INTRANS.-be-comforted.

the wreck the-spectacle-dire-of, (that)-it within

you awakened yes passion the-virtue-of,

I, by my art such-a-method-of

so safely have-controlled, that is not soul—

no, not hair-PART. on no being in the vessel

(that)-it you TRANS.-heard cry-ACC.

(that)-it you saw sink-ACC. down-sit,

because now you must know-ACC. further.

That's probably a lot to ingest all at once, so instead, here are some notes on specific things to look at:

- One thing that's actually interesting about this translation is that the word order does vary. So, in the first line, you'll see that a kind of retranslation would be, "It is the time that I you should inform further". That's kind of neat, given that there was no reason at all to change the word order.

- Another neat thing (and I don't know why I decided to do

this—it was completely spur of the moment, not planned, and not reflected in the grammar or structure of the language at all) is that I decided that possession of body parts should be inalienable. So the line that reads "wipe you eyes" is not a typo. What's happening is that the subject (or desired actor) of the command is being reintroduced after the verb (note that this can happen in older forms ofEnglish—like Shakespeare's—which is probably why it's in this translation), and "eyes" is inalienably possessed. So it's like, "Wipe the eyes", where "your" (and "the") is understood because the word "eyes" isn't preceded by the definite article. - As I mentioned, probably the major problem with Megdevi is the vocabulary. So, in the interlinear above, you'll see words that are defined as "lend", "pluck", "magic", "garment", "mantle", "spectacle", "dire", "passion", "virtue", "art", "soul", and "vessel". These are all very particular words. In the dictonary, they would be defined exactly this way. This means that there is an exact correspondence between the English word and the Megdevi. This is just impossible. Consider the word "magic". How could "magic" mean the exact same thing in any two languages? Also, look at the word for "soul". The Megdevi translation carries all the same connotations (e.g. a spirit in one's body, in the traditional religious sense, or a person, in the sense used here). There's just no way this could ever happen. Even cognates of the English word "soul" in related languages don't mean exactly the same thing. And as for a word like "garment", Megdevi had separate words for "garment", "article of clothing", "robe", "mantle", "shirt",

"cape"—the whole bit. This is evidence that little to no thought went into the lexicon of Megdevi. - Since I was pretty much translating the Shakespeare word-for-word, I didn't really think of the fact that, well, Shakespeare's English is different from modern English (and hopefully different from Megdevi, but that goes without saying). So in modern English, you really can't casually say, "You must know farther". First, it should be "further". Second, you wouldn't even say that, because it's just

bizarre—or antiquated. Had I been paying attention to that fact, I probably wouldn't have translated "farther" as a word which meant, well, "farther". - On the plus side, I didn't feel the need to translate "perdition" or "provision" (though I do believe there are words for both in Megdevi...).

- Also, note the fact that Megdevi allows double negation. This is the kind of thing that a typical first-time conlang will have. That is, there will be something very simple that's not allowed (or usually non-standard) in English, and, as a way to make the conlang "different", that feature will be allowed (but usually not required) in said conlang. So, here I just decided to allow double negation. I didn't think of how it would operate, exactly, or what implications that held for the rest of the language, because, as you can see, it works pretty much like in English (e.g. "No, not no hair on no one in the vessel", not "No, not no hair not on no one not in the vessel" [note also that it could be "no vessel" in both English and Megdevi]).

This should give you an idea of the problems of Megdevi. But notice that, syntactically and lexically, it can handle just about anything. Will the lexical choices be interesting? No. And the syntax? Well, to be quite honest, that preposition/clitic li- is just too powerful. It can do just about anything: Relative clauses, subordinate clauses, marking of an embedded object... That one little prefix is the main reason that Megdevi can translate anything. What is ordinarily difficult for a conlang is easy for Megdevi because of this one little kluge. It is artless, but it works. For that reason, it can translate anything, but the results just aren't desirable.

X. The Golden Knight: An Attempt at Megdevi Literature

Along with the language, I decided to write a book in Megdevi to give as a present to the girlfriend whose name this language bears. I was greatly inspired at the time by Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene, and what he was trying to do with it. In order to give the poem a particular feel, he elected not to write in modern English (his English), but to try to write in Chaucer's English. It doesn't come off as authentic (much too regular), but he did hit on something that seems to be true: you just can't write epics and allegories in modern language, whatever that modern language is. It seems like they should be written in an older language, or a different language. And so even though I felt this urge to write something like The Faerie Queene (because, dude, it's cool! Virginia Woolf knows what's up), writing it in modern day English felt kind of...stupid. So when I was working on the Megdevi script for the first time, I thought back to this blank book I'd won as a prize in tenth grade. I won it for being the best fiction writer in the class, and we had our pick of prizes (all sorts of things), but when I set eyes on that blank book (totally blank, 14 pages, 6.5" x 8.5"), I knew I had to have it. I had no idea what I was going to do with it, but the possibilities were endless. So I grabbed it up and saved it until, three or so years later, I figured out what to do with it: I was going to write an allegory in Megdevi.

Now there's an incredibly funny (read unbelievably frustrating) story that goes along with the making of this book. I wrote the story, of course, on the computer, originally. It was in a .txt document. I wrote out the script for each page in IPA, and then wrote out the English translation, along with an interlinear. I got all the way up to page...I don't know, 26 of 30? Sounds about right. In other words, I was nearly finished when disaster struck. I can't remember if I did something different, but I can't imagine I did. My computer crashed while I was working on it (nothing new for the old iMacs), and when I booted it back up, I couldn't open the file. There was no auto-saved version. This file was broken. I have never in all my years working with computers encountered a file that was more broken than this file. Nothing could open it. I think I even took it to a computer guy to try to fix it. Thus, all my work was lost, and I had to start over from scratch.

Don't you love when something like that happens? I should've saved that file for posterity, because of how broken it was. Oh well. Once I got over the, "Oh em gee, I have to do this all over again?!", I got to work, and it went quickly (after all, all the words I wanted had already been translated). Eventually I finished and got to illustrating it.

I'm by no means a good artist, evidenced by the fact that I adamantly refuse to use anything save Pentel's Color Pen S360 marker set (I especially hate painting). I've owned more than 10 sets of these over the years, and have been using

Thanks to my beloved scanner, the result can now be viewed on the web. There is no title, per se, but I refer to it as The Golden Knight, or Žii Žiilta Žeediv in Megdevi. I intended to write it in a specific meter, but gave up on it after the first sentence, which works (two like lines, followed by four left-over syllables; stress shown with underlines):

- ᴣediv baajs gænith pat bækil ᴣiiltæᴣ

- dᴣaratuu vaajn seliʃ ʔaheriʃuuθ kaaldᴣ

- ᴣiilta remiʃ.

- A knight of armor and shield of gold

- Was riding across a grass field upon

- A golden horse.

I guess the first syllable of the second line is extrametrical (why not?). In fact, because this line is so metrical, I can't seem to forget it, and can recall it from memory on command. Can't remember a single word of the rest of this book, but I've got this one down cold.

Below are the scanned images of the book. For each page below, there are two pages of the book. Recall that Megdevi is written from right to left, and, as such, the book starts at what would be the back for a book written in English, and you turn pages from left to right (as opposed to from right to left). So if you open pages one and two below, page one will be the one on the right, and page two will be the one on the left. I'm way too lazy to actually write a transcription, interlinear and translation down, so I just summarize the plot on each page and provide commentary. The images are cropped images. If you'd like to see the actual images, just remove the "x" at the end of each .jpg filename. They're huge (both space-wise and size-wise). If I ever do transcribe this beast, I'll use those pages to do it. Each of the links below will open up into a new, bare window. Click away!

[Note: If you're one of the eight people who currently use the internet without enabling JavaScript, please click here for a separate set of links to these pages.]

- A Picture of the Front Cover

- A Picture of the Back Cover

- A Picture of the Full Cover

- Pages 1 and 2 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 3 and 4 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 5 and 6 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 7 and 8 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 9 and 10 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 11 and 12 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 13 and 14 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 15 and 16 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 17 and 18 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 19 and 20 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 21 and 22 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 23 and 24 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 25 and 26 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 27 and 28 of The Golden Knight

- Pages 29 and 30 of The Golden Knight

So, there it is. Not too good; not too bad. Fun to make, though.

XI. What Now?

For those of you who might have a first conlang that seems similar in some ways to Megdevi, and this bothers you, there are obviously three options: (1) Leave it how it is and continue; (2) change whatever you think needs changing and continue; or (3) abandon it and move on. I'll comment on each of these.

First and foremost, this is your language, so if there are elements in it that are unnatural, but you like them, there's no reason to get rid of them. Additionally, though, every natural language has at least one feature that just seems fake. Though it's true that there's a lot of irregularity in languages, and that natural languages do things in creative ways, there are always facets of languages that are yawningly regular and seem totally uninspired. That's part of what makes language language. If everything was irregular, language would be unusable. So, for example, the lexical choices of Megdevi are pretty bad, so if I were to continue building on Megdevi, I'd feel like totally dumping all the vocabulary. I do, though, really like the way the verbs work, even though it was kind of hijacked from Esperanto and English. Thus, I'd probably leave them the way they were.

The next option is to change some things about the language. The goal is to change the problem issues but maintain the language's identity. So if I wanted to, I could totally just delete every lexeme of

And that's what I did with Megdevi. Why? Because every aspect of Megdevi is unsatisfactory to me. Every one: The phonology, the inflectional morphology, the derivational morphology, the triconsonantal root system, the nouns, the verbs, the adjectives, the lexicon: EVERYTHING. This doesn't mean that I don't like triconsonantal root

So what to do with it now? Well, it's described here, for reasons I already mentioned. Also, it's been used in conglang relays (the fourth, fifth and sixth), and is listed at Langmaker.com—it's even mentioned in Arika Okrent's book In the Land of Invented Languages—so people do know about it: It's out there. More importantly, though, some of the ideas I tried out in Megdevi inspired features in my other languages:

- The way that nouns and adjectives were derived in patterns in Megdevi directly inspired the Zhyler noun class system (which itself went on to inspire Dothraki).

- The bizarre "affricates" of Megdevi like [ks], [ps], etc. (along with the phonology of Skerre) helped inspire the phonology of Gweydr (in particular the plural suffix).

- The triconsonantal root system inspired the root system used in Tan Tyls.

- For a time, I was borrowing Megdevi words for advanced technology into Kamakawi. [Those forms have now been replaced with words from Zhyler.]

- Megdevi's freedom in word order was something I wanted to emulate in Sheli, though more realistically.

- The way I used Megdevi's script to write English definitely helped shape my views on orthography reform which led to the creation of the Petersonian English Alphabet.

- The lexical problems that Megdevi suffered from are what inspired my method for creating lexical items in Njaama.

- The way I went about creating

Megdevi—a pseudo-auxlang,almost—inspired Sathir, which, in a roundabout sort of way, is a critique of logicality and false opinions about language. - Making The Golden Knight gave me some experience with writing and illustrating these blank books I'm so fond of, which aided me greatly when I went on to start making children's books for my little sister.

So even though Megdevi is now a thing of the past, it did influence many of my other languages in different ways. In this way, though the language is abandoned, it's not dead, and certainly wasn't a waste of time. The same is true of any first-conlang that's abandoned. For even if later attempts are more developed and better in every way, nothing can beat the incredible intellectual rush of creating your very first language. That experience alone is useful and worthwhile. If keeping your old notes around can even for a moment allow you to recapture that initial enthusiasm, then those notes and that language, however incomplete, however imperfect, however derivative, are priceless.

XII. Miscellany

Every so often, members on the CONLANG listserv (past and present) hold a grand translation relay. It's essentially like a big game of telephone (cf. purple monkey dishwasher), only instead of one person saying a set phrase to another in English, each relay participant translates a text from someone else's conlang into their own, and then passes that on (go here for a more detailed description of the rules). It's great fun. And, as I'm an appreciator of fun, I've taken part in several conlang relays. Megdevi was a participant in three of the early relays, I'm sorry to say. I wish it hadn't, simply because it isn't any good, but you can't change the past. This is a list of the relays Megdevi's appeared in: